In 2021, it's almost taken for granted that the studio, whether that's a professional recording studio, a garage full of instruments and audio toys, or simply a laptop loaded with your software of choice, is as vital to the creation of a piece of music as any physical instrument or musical idea may be. This fundamental understanding of the studio's role in the creation of a recording is, however, still a relatively new concept. Even the concept of recorded music itself is still new when compared to the thousands of years when music was something that could only be experienced live, with each sound and note played by humans.

It really cannot be overstated how much the ability to record and play back sound has changed our understanding of music. With Edison's invention of the cylinder phonograph in the late 1800s, music was no longer solely an instantaneous art-form experienced in the moment, it was now an experience that could be repeated and heard in places far removed from where the sounds had originated.

As recording and playback technology evolved in the decades following this invention, an ever-increasing degree of creative control was placed in the hands of those doing the recording. The emergence of the engineer, as a technician who oversaw the transfer of a musical performance to a recording medium, marked the beginning of the studio becoming a compositional tool: it was now someone's job to make choices – aesthetic choices – regarding the sound of the recording.

Though it's arguably been an essential part of the process since the beginning of recorded music, the idea of the studio as a compositional tool really took hold with the establishment of tape as a recording medium in the 1940s. (http://www.discinternational.com/blog/re-record-dont-fade-away/) Today, the idea is evident in so many music genres, where the studio – with its wealth of digital audio capabilities – is arguably the most essential component of musical creation, allowing artists to piece together bits of audio from any number of sources and manipulate them to virtually limitless possibilities in creating musical compositions.

The idea is that the ‘studio is an instrument’ – that creating a musical recording is more than simply documenting a performance, and manipulating audio is itself an art-form. In this blog that originally appeared on Ableton.com we dig deeper into the pre-digital, pre-software history of this idea. Though not nearly all contributions can truly be accounted for, we've tried to distill this history down to a handful of key artists and accomplishments.

musique concrète

When discussing the evolution of the studio as a compositional tool, the work of French engineers/composers/sonic experimenters Pierre Schaeffer and Pierre Henry is a fine place to start. Schaeffer, who coined the term, and his frequent collaborator Henry are considered to be the foremost pioneers in the field of ‘musique concrète’, a method of composition in which pieces of recorded sounds (most often naturally occurring ones, rather than synthetic) are arranged into new musical contexts. Today, this concept may not sound particularly forward-thinking and provocative, but when Schaeffer and Henry began pursuing the possibilities of this collage-like approach to sound in the 1940s, they were definitely pushing the limits of the era's recording technology and, crucially, redrawing the conceptual lines of what could even be considered "music."

We would have seven or eight turntables playing together, but with only one sound playing on each,

In his earliest concrète experiments, Schaeffer (who had no musical background but decades of experience as an engineer for French broadcast radio) would record environmental sounds on to discs before returning to his studio to further isolate and manipulate the sounds. One technique he used was to etch these isolated sounds onto locked grooves – that is, records which grooves loop back into each other – allowing the material within the loop to be played indefinitely. "We would have seven or eight turntables playing together, but with only one sound playing on each," Schaeffer explained in an illuminating interview in 1986. "Then we would try different variations, montages with let's say, sound 'A' repeated twice, then a sound 'B' then 'C' repeated and so on," he continues, "It was similar to an orchestra rehearsal where you would be trying different themes, different variations."

The first composers to use magnetic tape not just as a means for recording and playing back music, but as an essential tool in creating a new type of composition.

The evolution of musique concrète was fundamentally tied to the rapid advancement of audio and recording technology in the post-World War II era, specifically, the development of the magnetic tape recorder (or simply, the tape machine). While working together at the Groupe de Musique Concrète (later renamed the Groupe de Recherches Musicales, or GRM), Schaeffer and Henry were formulating the earliest building blocks of modern day sampling by putting sounds onto tape, and then experimenting with different ways to manipulate those pieces of tape (varying speeds, playing sounds in reverse, making custom tape loops, etc.) in order to completely recontextualise the sounds. In essence, Schaeffer and Henry would become the first composers to use magnetic tape not just as a means for recording and playing back music, but as an essential tool in creating a new type of composition. The evolution of the studio as a creative tool was officially underway.

Etude aux Chemins de Fer (or "Railroad Study") became the first piece of musique concrète to be broadcast publicly in 1948. The concise collage strings together a number of sounds Schaeffer recorded at the Gare du Nord railway station in Paris, each individual sound being what the composer referred to as a "objet sonore" (or sound object): a sound removed from its contextual source and therefore allowed to inhabit its own existence within a composition.

Made of 22 movements and performed using an array of turntables and a mixer,

Considered the first masterpiece of musique concrète, Symphonie Pour Un Homme Seul (Symphony for a Man Alone) was first performed in 1950. Made of 22 movements and performed using an array of turntables and a mixer, the piece was shortened to just 11 movements for a broadcast in 1951. Stitching together bursts of machine and industrial noise, incomprehensible speech, spastic rhythms and frantic piano runs, Schaeffer himself referred to the composition as "an opera for blind people, a performance without argument, a poem made of noises, bursts of text, spoken or musical."

Bill Putnam and The Modern Studio

Born in Illinois in the early 1920s, Bill Putnam was an early architect of the modern recording studio. A seemingly tireless technical and musical mind, Putnam was drafted into service during World War II shortly after graduating from technical college. His service duties included both helping improve mine detection technology and recording big band performances for the Armed Forces Radio network. He also began writing for Radio and Electronics magazine where he detailed the inner workings of a 3-band EQ amplifier with independent boost and cut controls for highs, mids, and low frequency ranges; a now commonplace component in today's studios, Putnam's write-up marked the first time such an idea was put before a general public.

Putnam, along with contemporary recording luminaries Les Paul and Tom Dowd, would pioneer many of the techniques that would come to define modern record engineer:

After the war ended, Putnam decided to start his own business: an independent recording studio in Chicago's Civic Opera House. The business would also serve as a means for Putnam to create his own hardware under the name Universal Audio (yes, that Universal Audio) which would become ubiquitous in professional recording studios. And thus from the 1940s onward, Putnam, along with contemporary recording luminaries Les Paul and Tom Dowd, would pioneer many of the techniques that would come to define modern record engineer: amongst other things, they embraced the use of tape and multi-tracking, creatively deployed reverbs and delays, greatly advanced the technique of overdubbing, and began using drum booths and isolation to separate instruments onto discrete channels.

Putnam was one of the first engineers to realise that echo and reverb were not only just natural by-products of instruments playing in a room, but were in themselves elements of sound that could be created artificially and implemented artistically to enhance recordings. One of the most memorable instances of Putnam's ingenuity captured on record came early in his career with his recordings of The Harmonicats' "Peg O' My Heart" in 1947. A simple ditty led by a trio of chromatic harmonicas, Putnam turned the piece into a lush, dreamy recording with the use of artificial reverb. "Peg O' My Heart" was a massive hit and the first popular recording to use reverb in such a bold and artistic manner, enveloping the instruments in a generous cloud of reverberation created by the studio's echo chamber: the marble restroom at the Opera House.

As with many of these early developments in the history of the studio as an instrument, "Peg O' My Heart" doesn’t sound so radical to contemporary ears – a testament to how accustomed we have become to these once ground-breaking sounds.

Joe Meek on the Edge of Sound

Joe Meek's ascent to pop music prominence was swift but was ended abruptly by his early death (Meek took his own life in 1967 shortly after having shot his landlady). An outcast of sorts throughout his life – particularly as a homosexual man in a society that was still firmly entrenched in its heteronormative ways – Meek was tenacious when it came to getting the sound he wanted out of a recording, despite the fact that he was tone-deaf and could barely play any instrument.

Meek began his career in music at London's most advanced studio at the time, IBC, in 1955. There, Meek pushed the boundaries of acceptable practice within a rigidly hierarchical studio system where engineers still wore white lab coats. Among his repertoire of studio tricks, he was fond of using reflective surfaces to shape the recorded sound of certain instruments; he would often have horn sections play against a cement wall (in order to increase the early reflections), or move various surfaces around the studio to increase resonances, and made liberal use of the echo chambers available to him. Meek also made extensive use of compressors, often pushing them to the point of pumping and breathing. A stylistic choice for many producers these days, overloading compressors was, in Meek's time, simply using it wrong. But Meek heard something else.

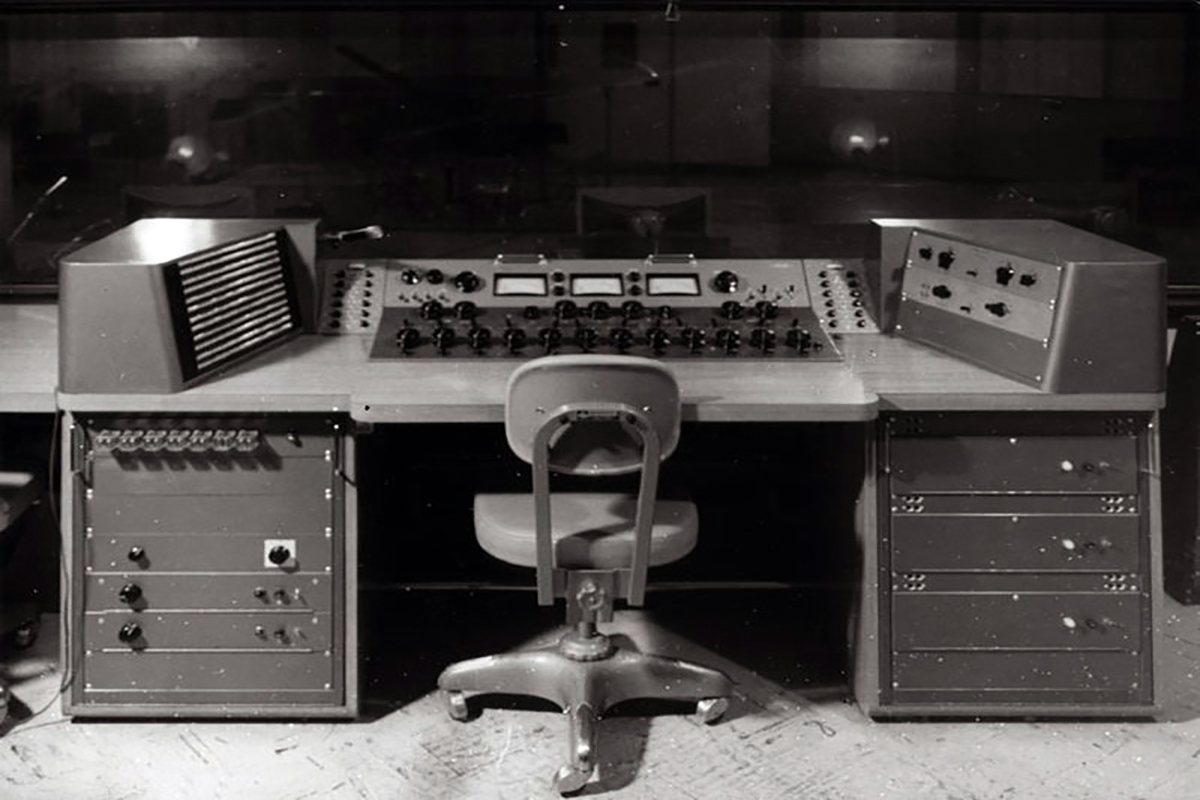

In part because of his insistence on pushing the studio equipment beyond what was accepted practice, Meek frequently butted heads with his employers. For this reason in 1960, Meek set up his own production company, RGM Sound Ltd, in a London flat at 304 Holloway Road. Here, Meek made some of his most renowned and commercially successful recordings while essentially also inventing the concept of a "home studio." Meek is said to have made use of almost every space in the flat, often attaching microphones to banisters using bicycle clips, spreading the musicians throughout different rooms and floors, and stocking his control room with an ensemble of custom-made audio boxes (referred to as Meek's "Black Boxes").

In 1962, Meek would produce his most famous recording at 304 Holloway, The Tornados’ "Telstar." Laced with space-age effects far ahead of its time – heavy feedback from a tape delay opens the song, while phasing, an effect achieved then by playing two tape decks simultaneously at altered speeds, appears throughout the instrumental tune – "Telstar" made use of several drum parts, two bass parts, three layers of Clavioline (spanning three octaves), a piano sped up on tape to sound like it was playing harp-like arpeggios, and a crystal-like solo guitar that fades in and out of the arrangement. A number one hit in the US and the UK, the song's unique sonic characteristics made it stand out on the pop charts and made a lasting impression on a generation of producers to come. Many of the same techniques would be put to use on an album which went ever farther out (but was far less successful than "Telstar"), Meek's own "outer space music fantasy” I Hear a New World.

A life lived on the edge of sound, Meek's tragic early death did not stop his influence from reverberating for decades to come, proven by the fact that the radical techniques Meek pursued in his time – placing microphones on instruments, using microphone selection to expand the sound palette, deploying compression for musical effect, and an openness to inventing new sounds to enhance compositions – are now all part of standard modern recording practice.

This post appeared originally on Ableton.com